George Oliver was the largest retailer of shoes and boots in the world.

George Oliver establishes a shoe retail business

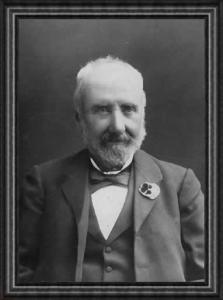

George Oliver (1836 – 1896) was born in Barrow upon Soar, Leicestershire, to humble circumstances. He was apprenticed to a cordwainer (shoemaker) in his native village.

Oliver opened his first shoe shop in Willenhall, Staffordshire in 1860. He employed three men by 1861. He opened a second shop with his brother Charles Oliver (1845 – 1897) in nearby Neath in 1868. Additional shops soon followed. The business catered towards the low-cost segment of the market.

George Oliver established a shoe factory in Wolverhampton in 1869, but it was sold in order to concentrate on the retail business in 1875. A distribution warehouse was established in Leicester. Oliver employed twelve men in 1881.

By 1889 there were over 100 shops, located in the more densely populated parts of Britain. George Oliver had one of the largest shoe retail businesses in Britain by 1896.

George Oliver had a shrewd mind and a keen business sense. His rugged exterior and brusque manner disguised a kindly personality. A keen Conservative and Freemason, he was a retiring man, renowned in Leicester for his generosity. He died from a sudden haemorrhage or stroke in 1896.

Charles Frederick Oliver takes over the business

George Oliver was succeeded in the management of the business by his brother Charles Oliver. A buoyant man with a genial temperament, he followed his brother by dying of a sudden haemorrhage or stroke in 1897.

Management of the business was taken over by George Oliver’s son, Charles Frederick Oliver (1868 – 1939).

In 1897 George Oliver advertised itself as the largest retailer of boots and shoes in the world, with 140 branches. Between 1915 and 1918 the firm claimed to be the largest footwear retailer in the world.

Charles Frederick Oliver was created a knight in 1933.

George Carter Oliver (1864 – 1935), a director of the firm and a son of George Oliver, died in 1935 with an estate valued at £158,206.

George Oliver was incorporated as a private company in 1936.

The third generation inherits the business

Sir Charles Frederick Oliver died in 1939, with a gross estate valued at £125,047. He was succeeded by his sons, Frederick Ernest Oliver (1900 – 1994) and Claude Danolds Oliver (1904 – 1987) as joint managing directors.

The family sold 36 percent of the company to the banking firm Robert Benson Lonsdale & Co in 1950 in order to pay the death duties of Lady Oliver.

George Oliver went public with a fully-paid share capital of £450,000 in 1954. Frederick Ernest Oliver was chairman. The business sold medium-priced footwear and hosiery for men, women and children. There were 111 branches, including 63 in England, principally in the South and West, and 48 in Wales. There were around 580 employees. Headquarters were at 18 Charles Street, Leicester.

F E Oliver was knighted in 1962 in recognition of his public and political service to Leicester. He was a modest, humble man. He retired from George Oliver in 1973.

George Oliver expands, and is acquired by Shoe Zone

With both firms suffering from the recession, George Oliver acquired Hiltons Footwear, a retail firm, for £9.8 million in 1981. Oliver had 130 branches and Hilton had 189, but only 25 overlapped. Oliver then sold and leased back 14 properties for £7.8 million to an investment group to fund the acquisition.

George Oliver had 1.7 percent of the British shoe retail market in 1986.

Timpson Shoes, with 228 shops, was acquired for £15 million in 1987. This doubled Oliver in size and created the third largest footwear retailing chain in Britain, with around 500 shops. The Timpson shoe shops were mostly located in Lancashire, Scotland, Teesside and Yorkshire, and only overlapped with Oliver in 30 locations. However they were not particularly profitable at the time of takeover.

George Oliver (now renamed the Oliver Group) acquired Frame Express, a London-based picture framing chain with 16 outlets for £1.8 million in 1989.

The Oliver Group employed around 4,000 people by 1989.

No members of the Oliver family worked at the Oliver Group by 1994.

The Oliver Group had become loss-making by 2000 and its estate of stores had been reduced to 258. The business was acquired by Shoe Zone of Leicester for £6.1 million. Oliver, Timpson and Olivers Timpson stores were rebranded under the Shoe Zone format. Loss-making outlets were closed.

As of 2020, the George Oliver name is still used as a Shoe Zone sub-brand.